A March 2019 study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) found whites experience 17 percent less pollution caused by their consumption of goods and services. On the other hand, Blacks and Hispanics experience 56 percent and 63 percent, respectively, more pollution than their consumption would generate. Whites experience a “pollution advantage” while Blacks and Hispanics experience a “pollution burden.”

This study builds on a growing body of environmental justice literature showing racial and ethnic disparities in air pollution exposure. It shows particulate matter (PM2.5) exposure in the U.S. is disproportionately caused by consumption patterns of whites and inhaled by people of color minority. Our Environmental Justice movement has been trying to change this and related environmental inequities for the past four decades.

While the study takes a somewhat different approach in examining disparities in air pollution exposure by examining consumption of goods and services, its findings once again reveal blacks and Hispanics bear a disproportionate “pollution burden” or costs, while whites experience “pollution advantage” or benefits. There is a clear disparity between the pollution white people cause and the pollution to which they are exposed. The study concludes, “pollution inequity is driven by differences among racial-ethnic groups in both exposure and the consumption that leads to the exposure.” There’s a name for this inequity. It’s called “environmental racism.”

This new study findings lend further evidence that blacks and Hispanic in the U.S. have the “wrong complexion for protection.” And we know what complexion that is: Black and brown. It also reaffirms that race is a potent predictor of exposure to goods and services air pollution. These findings also confirm what most grassroots environmental justice leaders have been fighting the past four decades, “whites are dumping their pollution on poor people and people of color.” The Transportation Justice Movement exposed racial disparities in car ownership and the unequal transportation-induced air pollution burden (which includes ozone, particulate matter, and other smog-forming emissions) borne by poor, people color and carless households in our cities.

Many grassroots and national environmental justice leaders have been fighting unfair, unjust and illegal land use policies and practices that turned their low wealth and people of color communities into toxic “hot-spots” and environmental “sacrifice zones” where even breathing the air, playing in parks and schoolyards can be dangerous to one’s health. Numerous environmental justice studies over the years detail the racial dimension of “pollution dumping.”

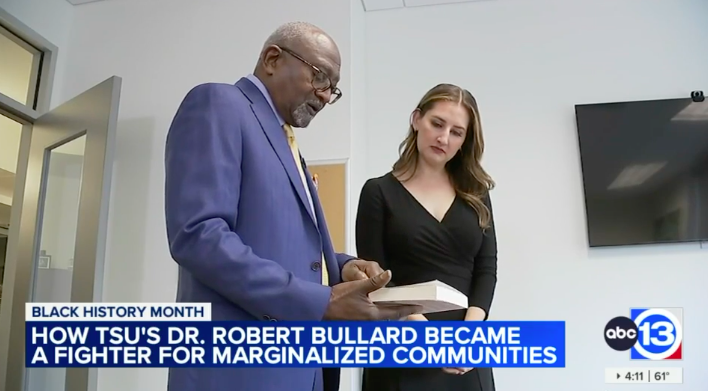

- Houston Solid Waste Study (1979). The “pollution advantage” for whites was documented more than four decades ago. Everyone produces waste, but everybody does not live near where the waste is disposed or dumped. There is a direct correlation between per capita income and waste generation (rich people per capita produce more waste than poor people). My 1979 Houston study (published in 1983) found a clear racial pattern in the city’s waste dumping: 82 percent of all solid waste disposed in Houston from the 1930s to 1978 was dumped in mostly black neighborhoods – even though blacks made up only 25 percent of Houston’s population. This pattern occurred in a city without zoning.

- Toxic Wastes and Race in the United States (1987). The first empirical study to document that was the most significant factor in the location of the nation’s hazardous waste facilities.

- Dumping in Dixie: Race, Class and Environmental Quality (1990). The first book published on environmental justice documented that environmental pollution and vulnerability map closely with race. Many of the nation’s environmental disparities have their roots in institutional racism and discriminatory zoning and land use practices.

- Toward Environmental Justice Research Education and Health Policy Needs (1999). The Institute of Medicine (later renamed National Academy of Medicine) study found people of color and low-income communities are exposed to higher levels of pollution than the rest of the nation; and these groups also contract certain diseases more than affluent white communities.

- Air of Injustice: African Americans and Power Plant Pollution (2002). More than 68 percent of African Americans live within 30 miles of a coal-fired power plant—the distance within which the maximum effects of the smokestack plume are expected to occur—compared with 56 percent of whites and 39 percent of Latinos who live in such proximity to a coal-fired power plant.

- Minorities Suffer Worst from Industrial Pollution (2005). The Associated Press three-part series revealed African Americans are 79 percent more likely than whites to live where industrial pollution pose” the greatest health danger. African Americans in 19 states are more than twice as likely as whites to live in neighborhoods with high pollution levels, compared to Hispanics in 12 states and Asians in 7 states.

- Toxic Wastes and Race at Twenty (2007). The follow-up study 20 years after the original study showed race is still the best predictor where commercial hazardous waste facilities are located; African Americans and other people of color make up most (56%) of those living in neighborhoods within two miles of commercial hazardous waste facilities; people of color make up over two-thirds (69%) of those living near clustered facilities; people of color are more concentrated in areas with commercial hazardous sites in 2007 than in 1987.

- Racial/Ethnic Differences in Exposure to Environmental Volatile Organic Compounds in the U.S. General Population: The National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1999-2000. (2008). The study found that race/ethnicity is associated with VOC exposure in that levels of total VOC exposure were higher for Mexican Americans and non-Hispanic blacks compared to non-Hispanic whites, both with or without adjusting for other socio-demographic variables.

- Race, Income and Environmental Inequality in the United States (2008). Even income does not insulate African Americans from elevated pollution assaults. African American households with incomes between $50,000 and $60,000 live in neighborhoods that are more polluted than the average neighborhood in which white households with incomes below $10,000 live.

- Coal Blooded: Putting Profits Before People (2012). The NAACP report found two million people live within three miles of the top twelve “dirtiest” coal fired power plants; 76 percent of these residents are people of color and the average per capita income is $14,626, compared with the national average of $21,587.

- Environmental Inequality in Exposure to Airborne Particulate Matter in the United States (2012). Overall levels of particulate matter exposure for people of color were higher than for whites.

- Population Surrounding 1,836 Superfund Remedial Sites (2013). The U.S. EPA found people of color are overrepresented in populations who live within a one-mile radius (44%) and a three-mile radius (46%) of the nation’s 1,388 Superfund sites. People of color comprise only 37 percent of the U.S. population.

- Communities Near Oil Refineries Must Demand Cleaner Air (2014). Half of the population that are at an increased cancer risk from oil refinery pollution for the 150 oil refineries in 32 states are people of color. People of color make up 37 percent of the U.S. population.

- Who’s in Danger: A Demographic Analysis of Chemical Vulnerability Zones (2014). The percentage of African Americans in the “fenceline zones” near chemical plants is 75 percent greater than for the U.S. as a whole, and the percentage of Latinos is 60 percent greater.

- Invisible Hazards Afflicting Schools (2014). One in every eleven U.S. public schools, serving roughly 4.4 million students, lie within 500 feet of highways, truck routes and other roads with significant traffic; 15 percent of schools where more than three-quarters of the students are racial or ethnic minorities are located near a busy road, compared with just 4 percent of schools where the demographics are reversed.

- National Patterns in Environmental Injustice and Inequality: Outdoor NO2 Air Pollution in the United States (2014). University of Minnesota researchers found African Americans and other people of color breathe 38 percent more polluted air than whites; people of color are exposed to 46 more nitrogen oxide than whites.

- Racial Isolation and Exposure to Airborne Particulate Matter and ozine in Understudies U.S. Populations: Environmental Justice Application of Downscaled Numerical Model Output (2016). Researchers found that long-term exposure to particulate matter is associated with racial segregation, with more highly segregated areas suffering higher levels of exposure.

- Disparities in Distribution of Particulate Matter Emission Sources by Race and Poverty Status (2018). This EPA study found people of color in 46 states live with more air pollution than whites; African Americans are exposed to 1.54 times more fine particulate matter than whites; Hispanics are exposed to 1.2 times; those below poverty are exposed 1.35 times more than those above poverty. Again, race was more powerful than income.

Pollution is taking a heavy toll on the health of African Americans and other people of color. For example, a 2017 Harvard University study found African Americans are nearly three times more likely to die from exposure to airborne pollutants than other Americans. According to the CDC, African Americans are almost three times more likely than whites to die from asthma related causes; African American children are 4 times more likely to be admitted to the hospital for asthma, as compared to non-Hispanic white children; African American children have an asthma death rate ten times that of non-Hispanic white children. Dismantling institutional racism would go a long way in closing environmental health disparities in the United States. It’s time for this immoral, unjust and illegal pollution dumping to end.