The eight-year war against toxic racism is nearly over for Sheila Holt Orstedandthe Harry Holt family, an African American family in Dickson, Tennessee whose well was poisoned with trichloroethylene (TCE) from the nearby leaky Dickson County Landfill, located just 54 feet from the family’s property line.Five generations of Holt family members grew up in the rural all-black segregated community on Eno Road in Dickson County. The Holt family survived the horrors of slavery and “Jim Crow” segregation, but it may not survive the toxic terror of the deadly trichloroethylene (TCE) chemical leaked into their wells from the nearby landfill.In 2003, the Holt family and the NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund (LDF) sued the city and county of Dickson, the state of Tennessee, and the company that dumped the TCE. And in 2008, the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC), Sheila Holt Orsted and her mother Beatrice Holt filed a lawsuit against Dickson City and County governments seeking cleanup of alleged water contamination.

After a protracted legal struggle, on December 7, 2011, a $5.6 million settlement agreement was finally reached with the Dickson City and County governments on the NRDC and Holts’ suit and a $1.75 million settlement to be paid to eleven Holt family members on the family’s NAACP civil rights suit with monies from an October settlement reached with three companies that were defendants in the Holts’ NRDC case. Ironically, the county spent more than $3 million and the city almost $1.9 million on the lawsuits.

In response to the Holts’ demand for a personal apology from the City and County of Dickson, the settlement agreement includes the following statement: “The county and city regret the Harry Holt family well was contaminated with TCE and the issues experienced by the Holt family.” One would have to assume the “issues” the city and county government officials are alluding to in their statement refer to the fact that the Holt family’s well water was poisoned by a city and county owned toxic landfill and the fact that the Holt family members are sick and some have died. Harry Holt died of cancer in January 2007. His daughter, Sheila Holt Orsted is recovering from breast cancer.

The industrial solvent TCE is widely known to be harmful to humans. A 2011 EPA study found that TCE is even more dangerous to people’s health than previously thought—causing kidney and liver cancer, lymphoma and other health problems. This new EPA study lays the groundwork to reevaluate the federal drinking-water standard for TCE: 5 parts per billion in water, and 1 microgram per cubic meter in air.

Despite the recent settlement agreement, the Holt family’s toxic nightmare on Eno Road, described in the 2007 Toxic Wastes and Race at Twenty report as the “poster child” for environmental racism, is not yet over. Nor is their quest for environmental justice complete since the state of Tennessee, a defendant in the Holts’ civil rights case, has not worked out a settlement. The case is scheduled to go to trial next year.

The Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation (TDEC) is the chief environmental and natural resource regulatory agency in the state. With its $426 million annual budget and 2,900 employees, TDEC is charged with “safeguarding the health and safety of Tennessee citizens from environmental hazards and protecting and improving the quality of Tennessee's land, air and water.” The Harry Holt family members are law-abiding Tennessee citizens who deserve to be protected just like other Tennesseans.

The mission of TDEC’s Division of Solid and Hazardous Waste Management is to “protect and enhance the public health and environment from existing and future contamination of the land through proper management and remediation of solid and hazardous wastes.” Clearly, this state program failed the Holt family. Dickson County covers more than 490 square miles. Yet, all of the solid waste landfills in Dickson County permitted by the state of Tennessee are located in the mostly black Eno Road community. This is no random accident since African Americans make up only 4.1 percent of the Dickson County population.

Government records show that the state of Tennessee approved the Dickson County Landfill permit on December 2, 1988—even though test results completed on November 18, 1988 on the Harry Holt well showed TCE contamination. On December 8, 1988, the state sent a letter to Harry Holt informing the family of the test results and the finding of trichloroethene in his well. The letter states: “Your water is of good quality for the parameters tested. It is felt that the low levels of methylene or trichloroethene may be due to either lab or sampling error.”

Two years later, on January 28, 1990, government tests found 26 ppb (parts per billion) TCE in the Harry Holt well, five times above the established Maximum Contaminant Level (MCL) of 5ppb set by the federal EPA. The MCL is the maximum concentration of a chemical that is allowed in public drinking water systems. A year later, on December 3, 1991, the federal EPA sent the Harry Holt family a letter informing him of the three tests performed on his well and deemed it safe. The letter states: “Use of your well water should not result in any adverse health effects.” The letter further states: “It should be mentioned, that trichloroethylene (TCE) was detected at 26 ug/1 in the first sample. Because this detection exceeded EPA’s Maximum Contaminant Level (MCL) of 5 ug/1, the well water was resampled. TCE was detected at 3.7 ug/1 in the second sample, however, it was noted this sample contained air bubbles.” EPA then took a third sample with results nearly identical to the second (3.9 ug/1).

Although the Holts’ well was evaluated in 1991 as “safe” by the EPA, state officials continued to discuss the TCE contamination among themselves and with EPA officials in 1991 and 1992 internal memoranda. On December 17, 1991, an internal TDEC memorandum expressed concern about the level of TCE contamination found in the Holt’s well. The state officials agreed that Mr. Holt’s well should continue to be sampled as a precaution. The letter states: “Our program is concerned that the sampling twice with one considerably above MCL and one slightly below MCL in a karst area such as Dickson is in no way an assurance that Mr. Holt’s well water will stay below MCL’s. There is a considerably seasonal variation for contaminants in karst environments and 3.9 ppb TCE in only slightly under the MCL of 5 ppb.” Although state officials expressed concern, they took no action to protect the Holt family and allowed them to continue drinking TCE contaminated well water.

A January 6, 1992 TDEC memorandum continued to express concern about the level of TCE contamination found in the Holts’ well. The letter states: “Mr. Holt’s well was sampled as a result of the Preremedial Site Investigation and Ranking package on the Dickson County landfill for NPL consideration. Mr. Carr told me the field investigation was complete and that he was not in a position to sample Mr. Holt’s well again even though it had sporadically shown TCE contamination above MCL’s. He agreed that Mr. Holt’s well should continue to be sampled. There may be some chance of the site going NPL, but that will be at least 1-2 years away. Mr. Carr suggested I contact Nathan Sykes at (404) 347-2913 to determine why it was not felt that further monitoring or an alternate water supply was necessary.” No additional follow-up sampling was conducted by the state and no alternative water supply was provided the Holt family.

A March 13, 1992 TDEC memorandum eventually sides with EPA on the Holt family well water being “safe.” The letter states: “Since EPA has already completed a site investigation, has identified the pollutants involved, and has, in part, determined the extent of the leaching, I would suggest that they, EPA, continue with their chosen course of action, rather than create the added confusion of various agencies making their own agendas. I would suggest that, if Mr. Holt is concerned about possible health risks in using his well water between now and June (when EPA’s priority decision is made), that he should rely on bottled or city water for cooking and drinking purposes until he is convinced that his well water is safe.” Unfortunately, the Holts were not privy to these internal memoranda and discussions between the state and EPA officials about the safety of their well water. Not having this information, the Holt family continued to drink water from their well.

The way the state responded to black families and white families is like night and day. In 1993, nine white families in Dickson were found to have TCE contaminated wells. A detailed written action plan was developed for each family. The families were notified by the state within 48 hours of that determination and informed not to drink the well water. On March 2, 1994, TCE was detected in a spring used by two white families. On September 2, 1994, state officials notified the white families in writing that “they should not use the water for drinking until further notice.” The white families were immediately provided bottle water and later placed on the city water system.

An alarm should have gone off on February 2, 1997 when the state detected TCE in a production well (DK-21) operated by the City of Dickson and located northeast of the landfill. The Harry Holt well lies between the leaky landfill and the DK-21 well. And on April 4, 1997, the city stopped using the DK-21 well as a supplement to the municipal water source after a call from the state. It seems a bit strange that the Holt family well was not monitored each year as state officials recommended and after TCE was detected in 1991 and after TCE was found at the DK-21 well in 1997. According to the 2004 Dickson County Landfill Reassessment Report (see Table 2) prepared by Tetra Tech EM, Inc. for EPA, the Harry Holt well was not tested at all between 1992-1999. The question is Why?

The Holts’ well was not retested until October 9, 2000—when it registered a whopping 120 ppb TCE, 24 times higher than the Maximum Contaminant Level (MCL) of 5ppb set by the federal EPA. The Holt family was placed on Dickson City water on October 20, 2000—twelve years after the first government tests found TCE in their well in 1988. And on October 25, 2000, a second test performed on Harry Holt well registered 145 ppb—24 times higher than the MCL. This “dirty justice” is unacceptable. Tennessee needs to step up and do the just, fair and right thing by the Harry Holt family. This well of pain must end now! The Holt family has suffered enough.

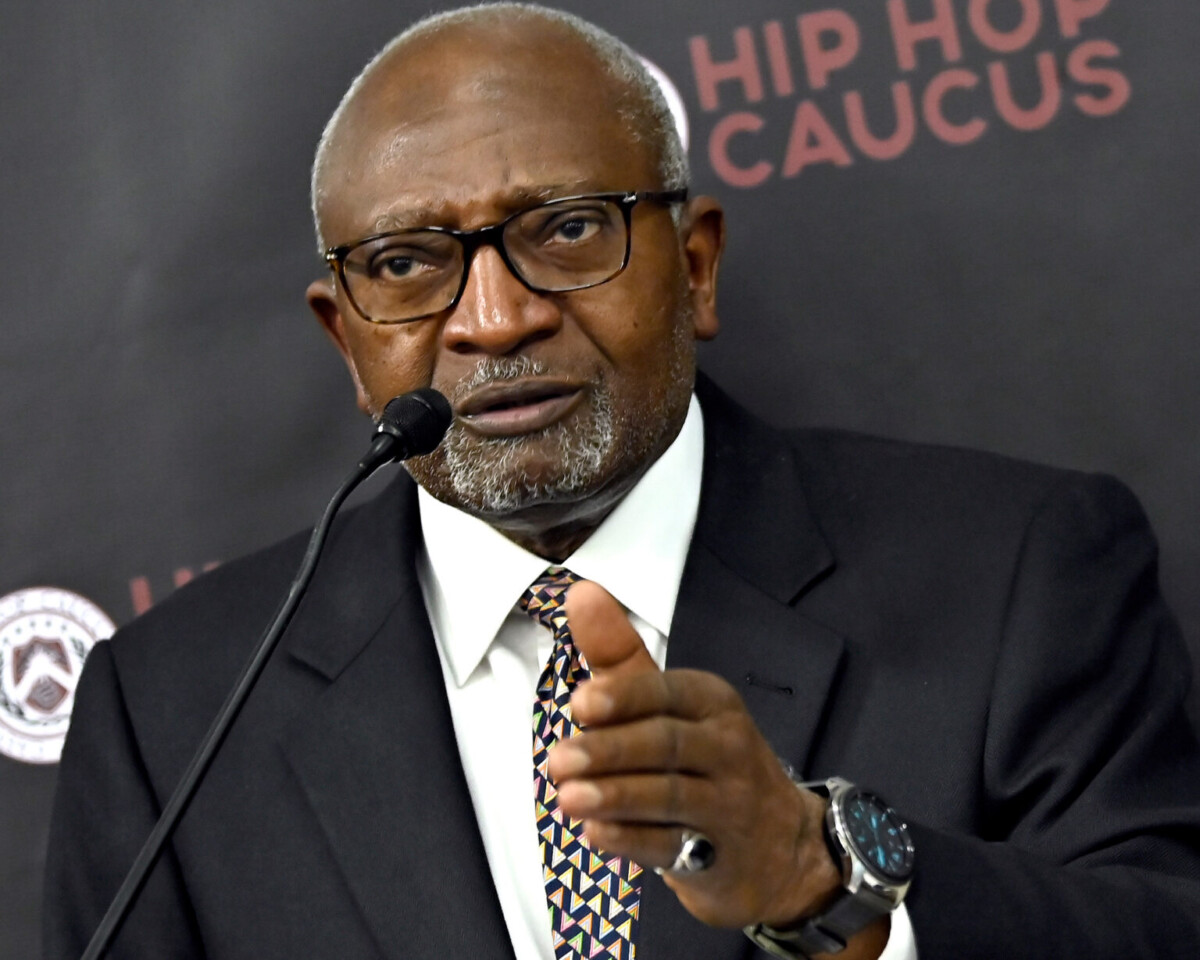

MSU Sociology!: Renowned environmentalist Dr. Robert D. Bullard speaks on campus as part of Kaplowitz Lecture Series

The College of Social Science welcomed Robert D. Bullard, PhD...