HOUSTON, Texas – February 9, 2014 – On Tuesday environmental justice groups and coalitions from around the country will commemorate the twentieth anniversary of the historic Environmental Justice Executive Order 12898 “Federal Actions to Address Environmental Justice in Minority Populations and Low-Income Populations” signed by President Bill Clinton.

HOUSTON, Texas – February 9, 2014 – On Tuesday environmental justice groups and coalitions from around the country will commemorate the twentieth anniversary of the historic Environmental Justice Executive Order 12898 “Federal Actions to Address Environmental Justice in Minority Populations and Low-Income Populations” signed by President Bill Clinton.

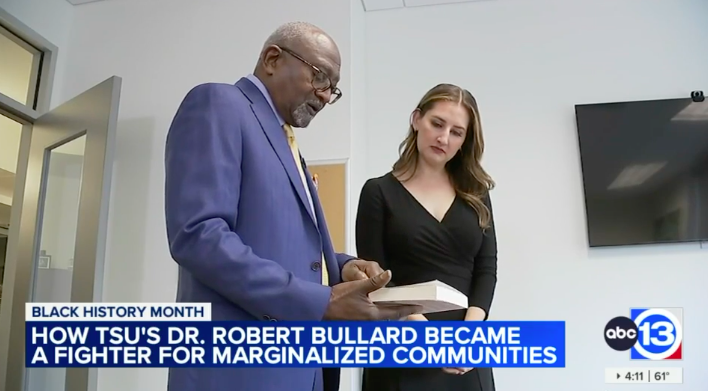

As part of the 20-year anniversary, a team of researchers from the Barbara Jordan-Mickey Leland School of Public Affairs at Texas Southern University released Environmental Justice Milestones and Accomplishments: 1964-2014,”a report that chronicles environmental justice milestones, accomplishments and achievements of the Environmental Justice Movement in the United States over the past five decades, beginning with the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 signed by President Lyndon B. Johnson. The report is sheduled to be released on Tuesday February 11.

After decades of hard work, struggle, and some victories along the way, the quest for environmental justice for all communities has yet to be achieved. Even in 2014, the most potent predictor of health is zip code. Race and poverty are also powerful predictors of students who attend schools near polluting facilities, the location of polluted neighborhoods that pose the greatest threat to human health, hazardous waste facilities, urban heat islands, and access to healthy foods, parks, and tree cover.

Transportation equity remains a major environmental justice and civil rights challenge. The nation’s transportation, energy, climate and disaster management policies have a long way to go to ensure just and equitable benefits accrue to low-wealth and people of color communities, while at the same time not allowing the negative impacts to flow disproportionately to these same communities. Environmental justice leaders want to see these gaps closed now and not have to wait another two decades.

The Executive Order after twenty years and three U.S. presidents (Bill Clinton, George W. Bush and Barrack Obama) has never been fully implemented. Still, the environmental justice movement has made tremendous strides over the years. Out of the small and seemingly isolated environmental struggles, emerged a potent grassroots community driven movement that is now a global movement.

In 1994, only four states (Louisiana, Connecticut, Virginia, and Texas) had a law or an executive order on environmental justice. In 2014, all 50 states and the District of Columbia have instituted some type of environmental justice law, executive order, or policy, indicating that the area of environmental justice continues to grow and mature.

In 1990, Dumping in Dixie was the first and only environmental justice book. In 1994, there were fewer than a dozen environmental justice books in print. Today, hundreds of environmental justice books line the shelves of bookstores and classrooms covering a wide range of disciplines. Environmental justice courses and curricula can be found at nearly every college and university in the U.S.

The number of people of color environmental groups has grown from 300 groups in 1992 to more than 3,000 groups and a dozen national, regional and ethnic networks in 2014. Prior to 1994, only a couple of EJ leaders had won national recognition and awards for their work. In the past twenty years, more than two-dozen environmental justice leaders have won prestigious national awards, including the Heinz Award, Goldman Prize, MacArthur “Genius” Fellowship, Ford Foundation Leadership for a Changing World Award, Robert Wood Johnson Community Health Leaders Award, and others. For example, Hilton Kelly, who directs Community In-Power and Development Association (CIDA), won the 2013 Goldman Prize for his environmental justice work in addressing pollution near oil refineries in Port Arthur, Texas. And in 2014, Kimberly Wasserman Nieto of the Little Village Environmental Justice Organization (LVEJO) won the Goldman Prize for her collaborative work in shutting down the Fisk and Crawford coal plants in Chicago.

The movement is still under-funded after decades of proven work. This is true for private foundation and government funding. Overall, foundation and government funding support for environmental justice has been piecemeal. Environmental funders spent a whopping $10 billion between 2000 and 2009. However, just 15 percent of the environmental grant dollars benefitted marginalized communities, and only 11 percent went to advancing “social justice” causes, such as community organizing.

After years of hard work, struggle, and some victories along the way, the quest for environmental justice for all communities has yet to be achieved. Even in 2014, the most potent predictor of health is zip code. Race is still the most powerful predictor of locally unwanted land uses or LULUs and access to healthy foods. The EPA’s Plan EJ 2014 is a roadmap that will help the agency integrate environmental justice into its programs, policies, and activities over the next 20 years. Because of the historic milestone, EPA Administrator Gina McCarthy declared February “Environmental Justice Month.”

The vast majority of environmental justice leaders two decades ago preferred to have environmental justice codified in law. However, that did not happen. As part of the commemoration, reactions were solicited from environmental justice leaders representing diverse stakeholder groups from activists to academics. We asked the following question: “What is the state of the Environmental Justice Executive Order and the Environmental Justice Movement?” Here is what others have to say about the Executive Order at twenty:

What Others Are Saying About the Executive Order and the EJ Movement

The focus of the environmental justice movement is now just and sustainable development. This means using our unlimited mental and creative resources, not our limited natural resources. If this is true, as I believe it to be, then we need to develop more constructive ways to unleash these phenomenal mental and creative resources in our communities, and quickly. Currently, in the US and around the globe we waste human potential as wantonly and comprehensively as we lay waste to our environmental potential, and this is no surprise, as both actions are directly related. We need to understand that while there is growing human inequality, there will never be environmental quality. (Julian Agyeman, Ph.D., FRSA, Department of Urban and Environmental and Policy Planning, Tufts University, Medford, MA)

The Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law has promoted environmental justice for many years. The most recent example of its work in this area grew out of a request from fair housing advocates in Texas who are monitoring implementation of a disaster recovery program funded by HUD. They reached out to the Lawyers’ Committee for assistance in appraising housing proposals in Port Arthur TX to replace low income, predominantly African American public housing projects which abutted an area with dozens of petrochemical refineries that had steadily expanded over the years to become the largest concentration of refineries in the country. Indeed, in 2009, Port Arthur was named an “Environmental Showcase Community” by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (“EPA”) which concluded that relocation of the residents of low income predominantly African-American public housing projects damaged by Hurricane Ike should be a high priority because of the environmental dangers posed by the refineries. Working with the organizations that are monitoring the disaster recovery program, the Lawyers’ Committee is providing legal assistance to ensure replacement housing is environmentally safe. (Barbara Arnwine, President and Executive Director, Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law, Washington, DC)

While there has been some progress in environmental justice, much remains to be done. The federal legal foundation is still very weak, based as it is on Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, color, and national origin, by recipients of federal financial assistance. There are almost no federal discrimination protections on the basis of low income, which the EJ Executive Order addresses. There needs to be a statutory basis for EJ protections, which includes low income. (Marc Brenman, The Evergreen State College, Olympia, Washington)

The Executive Order on EJ is a sham. The only thing the EO has produced is jobs for the people at these federal agencies tasked to create the illusion that they are working to achieve environmental justice. I have witnessed heartless and clueless representatives of federal agencies visit hardcore EJ communities and board their plane back to DC untouched, unmoved and, despite numerous attempts on our part, were never heard from again. I have witnessed good people at federal agencies that wanted to truly help. But, before they could do anything significant they were removed from their position, or lost their job. The only ones celebrating the 20th anniversary of the EO is the federal government for succeeding to put on the biggest fraud and sin against EJ communities everywhere. (Suzie Canales, Executive Director, Citizens for Environmental Justice, Corpus Christi, TX)

Here in Oregon, our legislature passed a law requiring all natural resource agencies to include EJ in their official actions, and created the EJ Task force to report on whether they do so. Without E.O. 12898, environmentalists do not recognize EJ. Without E.O. 12898, sustainability advocates do not include equity. There is a color line between environmentalism, sustainability and environmental justice — and the color of that line is not green. E.O. 12898 is an essential foundation for recognizing the single, unified nature of these struggles. I was the founding chair of the Oregon EJ Task force. (Robin Morris Collin, Norma J. Paulus Professor of Law and Director of the Certificate Program in Sustainability, Willamette University, Salem, OR)

The most immediate mission of the EJ movement is to dismantle the mechanisms by which capital and the state disproportionately displace ecological hazards onto poorer communities and people of color. One of the movement’s most important accomplishments has been President Clinton’s Executive Order (12898) on Environmental Justice. Despite bringing some substantial improvements to many communities, however, the Executive Order is primarily about “identifying and addressing, as appropriate, disproportionately high and adverse human health or environmental effects of their programs, policies and activities on minority populations and low income populations” rather than eliminating the root causes of such ecological hazards. But the struggle for environmental justice is not just about distributing environmental risks equally but about preventing them from being produced in the first place so that no one is harmed at all. What is now needed for the 21st Century is a richer conception of environmental justice oriented toward a major transformation of the U.S. (and global) economy. Such a conception includes the phase-out of toxic chemicals and fossil fuels in favor of clean production and energy systems, efficient public transportation, affordable housing and vibrant communities, green jobs and full employment at a living wage, and more precautionary and sustainable approaches to environmental policy. In this sense, the Executive Order is a necessary ingredient but in-and-of-itself insufficient for achieving true environmental justice. The challenge confronting the EJ movement is to help forge a truly broad-based, multi-issue, multi-movement approach which emphasizes social and eco-justice for all Americans and people around the world…both present and future generations. (Daniel Faber, Ph.D., Director, Northeastern Environmental Justice Research Collaborative Northeastern University, Boston, MA)

Twenty years ago President Clinton authorized the federal government to address environmental justice in its programs and policies. President Obama renewed that authority when he came into office. While Clinton’s Executive Order and Obama’s reauthorization provide a framework for addressing environmental injustice, that framework has not resulted in concrete changes in environmental justice communities. Rather, it is the communities themselves working together as part of the environmental justice movement that have brought about the pollution reductions, clean green jobs, sustainable community plans, and environmental benefits that communities experience. The federal government has much more to do to catch up to progress communities have made and to follow through on its comment to environmental justice. (Caroline Farrell, Executive Director, Center on Race, Poverty & the Environment, Delano, CA)

The Executive Order’s longevity is a major landmark. After 20 years, environmental justice is a familiar phrase in the nation’s capital, the fifty states and around the world. Community advocates achieved this milestone but their fight for it at home goes on. Now, we need legislation that fills the gaps and a Marshall Plan that ensures clean, healthy and prosperous neighborhoods for everyone. (Deeohn Ferris, J.D., President, Sustainable Community Development Group, Washington, DC)

The EJ movement has been the conscience of the environmental movement. The EJ movement has been about making a way when there has been no way. Through the unceasing activism of affected communities and stalwart supporters of these communities, the EO 12898 has been utilized to move federal (and other) stakeholders to make EJ central to their decision-making. Much more work needs to be done by the other agencies in the Interagency Working Group (IWG) on EJ. Hopefully, this anniversary will spark a greater commitment by the other agencies in the IWG to comply with the EO 12898. Congratulations, on this anniversary, to all the EJ activists and supporters who have seriously struggled with making the EO 12898 work within the agencies and for the affected communities. (Leslie Fields, National Environmental Justice Director Sierra Club, Washington, DC)

It has been twenty years since President Bill Clinton issued his executive order on environmental justice. The executive order itself reflected the growing strength of a movement centered among the poorest and most racially unequal communities in the nation. Regrettably, little has changed with regard to the practices of the federal government since the order was issued. Nevertheless, the environmental justice movement has achieved remarkable successes at the local and regional level – mobilizing hundreds of thousands of people to close coal fired power plants, to stop oil refinery projects, to expand clean energy infrastructure, to expand green space, urban gardens, and sustainable agriculture, to safeguard and expand public transportation. Most importantly, they have enhanced US democracy, but creating spaces where those most affected by pollution, toxic emissions, and climate change impacts can have their voices heard in a meaningful way. This is the incredible foundation on which the environmental justice movement will continue in its efforts to protect the health of our children and our communities, to address the systemic inequality that continues to plague our country, and ultimately to save our planet. It is my hope that President Obama will give new meaning to the Executive Order in his final years in office, by ordering its effective implementation in all federal departments. Si Se Puede! (Bill Gallegos, Executive Director, Communities for a Better Environment, Oakland, CA).

The President’s Executive Order 12898 on Environmental Justice is greening Los Angeles. Federal agencies are not just talking about the EJ Executive Order, they are taking action. The National Park Service recognizes there are unfair disparities in park access for people who are of color or low-income people, that these disparities hurt human health, and that park agencies need to promote equal access to parks and active living for all, citing the EJ Order. NPS has published a strategic action plan, and a science plan, for Healthy Parks, Healthy People. NPS recommends new national recreation area lands in the San Gabriel Mountains and Valley to promote environmental justice and health. The Army Corps of Engineers proposes greening the Los Angeles River to promote environmental justice and health, citing the EJ Order. Andrew Cuomo, who was then Secretary of the US Department of Housing and Urban Development, withheld federal funding for a proposed warehouse project in the heart of downtown Los Angeles unless there was full environmental review that considered the park alternative and the impact on people who were of color or low income. Secretary Cuomo cited the EJ Order and Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, acting in response to an administrative complaint filed by diverse allies. The site could have been warehouses. Instead, today it’s the Los Angeles State Historic Park. Attorneys, activists, and agencies are working together for healthy green land use, equitable development, and planning by and for the community under the EJ Order. Let’s do it! (Robert Garcia, Founding Director and Counsel, The City Project, Los Angeles, CA)

The Environmental Justice Movement in the United States included the voices of American Indian and Alaska Native nations and their grassroots indigenous communities and families to stand fast in defense of the vital life cycles of Mother Earth. After twenty years since the EJ Executive Order 12898, with the perseverance of tribal governments and Native environmental organizations, “Indian” policy in environmental protection, public health, protection of sacred areas and conservation of natural resources within indigenous lands and territories were strengthen and further developed. The link between environmental justice, treaty rights with a rights-based approach in organizing; applied along with the demand for the U.S. to fulfill its fiduciary and trust responsibilities to federally recognized tribes to build their tribal infrastructure for environmental protection was the broad voice of victory of many Native Nations. The twenty years of the Native-based environmental justice movement was largely led by grassroots Indigenous peoples with many victories, but remaining challenges in the crosscutting issues of continued struggles for energy and climate justice; food sovereignty; water rights; economic justice and for the full implementation by the U.S. of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. The next twenty years, we must link social and environmental struggles, bring together rural and urban communities, and combine local and global initiatives so that we can unite together in a common struggle. We must use all diverse forms of resistance. We must build a movement that is based on the daily life of people that guarantees democracy at all stages of societies. (Tom Goldtooth, Executive Director of the Indigenous Environmental Network, Bemidji, MN)

The EJ Executive Order helped focus agency and public attention on the incidence of race-based environmental inequality, and provided greater basis for redress of the most egregious cases of environmental racism. However, it is important to remember that capitalist economies are predicated on the distribution of social goods and bads by wealth. Just as housing, food, and higher education, environmental hazards and amenities are, and will continue to be, distributed by economic class. And as long as class remains correlated with race, environmental hazards will continue to be distributed disproportionately to people of color. The EJ Executive Order was an important milestone on what will be a very long road to environmental justice. (Kenneth Gould, Ph.D.., Professor of Sociology, Brooklyn College-CUNY, Professor of Sociology and Earth and Environmental Sciences, CUNY Graduate Center, Brooklyn, NY)

In 1994, when President Bill Clinton signed EJ Executive Order 12898 many of the grassroots activists felt ‘environmental justice’ (EJ) was finally being recognized and substantive actions would be taken to clean up communities and relieve suffering caused by environmental insults of various kinds. Executive Order 12898 paved the way for justice but didn’t guarantee it. Undoing past wrongs, such as cleaning up dumpsites, changing siting habits, and changing lax rules and regulations to better protect communities, in many cases hasn’t happened. Environmental Justice has been steered by the political tide over the tenure of the past three Presidents while many state and local authorities continue to dig their heels in even deeper to avoid adequately addressing EJ issues. Even though some states have so-called EJ staff, they have not worked to sufficiently alleviate suffering and bring about justice in struggling communities. We lost a great deal of momentum for EJ during the Bush Administration, which made the states bristle against effectively addressing EJ even more. During the Obama Administration, we are trying to regain the momentum we once had, and try to move more aggressively to work on a backlog of EJ issues. However, even in the Obama administration the rise of the Tea Party is working to hinder EJ activities, block the strengthening of environmental laws, and strike against any efforts toward sustainability and/or environmental justice. Our efforts need to be re-doubled. (Rita Harris, Sierra Club EJ Program, Memphis, TN)

The Executive Order on EJ was an historic act that helped to awaken the consciousness of our federal government to the long-standing suffering in low-income communities and communities of color across the country facing environmental racism and economic injustice. Unfortunately, twenty years later we still have communities across the country that are unnecessarily exposed to toxic pollution that threatens their health and quality of life. Many of these communities also lack basic environmental benefits too like a healthy home free of toxins, access to open spaces like parks, the availability of healthy foods, and safe and affordable public transportation. So on this anniversary, our collective struggle for justice continues and our voices grow louder and stronger. (Al Huang, Senior Attorney and Director of Environmental Justice, Natural Resources Defense Council, New York, NY)

Even now 20 years after the signing of the ‘Environmental Justice Executive Order’, communities in Louisiana’s Cancer Alley are still fighting for justice and a safe future for their communities. (Daryl Malek-Wiley, Sierra Club Environmental Justice & Community Partnership Program, New Orleans, LA)

As a relatively new EJ community activist and advocate, I am so impressed and grateful to those who have blazed the trail over the past twenty years — you’ve set an awfully high standard for us new comers! As we all share in the joy of this well-deserved celebration, may we be committed to utilizing all of the accomplishments to inspire and empower our work in the days ahead. Special thanks to all of our courageous, hard-working, committed EJ pioneers. (Margaret J. May, Executive Director, Ivanhoe Neighborhood Council, Kansas City, MO)

The President’s 1994 Environmental Justice Executive Order is the high water mark in federal policy making regarding Environmental Justice in the U.S. It is also a testament to the rapid rise, potency, and enduring nature of the Environmental Justice movement. The Executive Order is indeed the culmination of the progression of potent and rapidly unfolding events. From the 1982 Warren County, North Carolina, protests, to the 1987 United Church of Christ report, Toxic Wastes and Race in the United States, to Robert Bullard’s 1990 book, Dumping in Dixie, to the 1990 Michigan Conference, to the 1991 National People of Color Environmental Leadership Summit that produced the 17 Principle of Environmental Justice, to Bunyan Bryant and Paul Mohai’s 1992 book, Race and the Incidence of Environmental Hazards, to the U.S. EPA’s 1992 report, Environmental Equity: Reducing Risks for All Communities, to the 1994 Executive Order, a high water mark was achieved within a twelve-year span and has endured as the foundation of Environmental Justice Policy in America under three Presidential Administrations. (Paul Mohai, Ph.D., School of Natural Resources and Environment, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI)

The 20th Anniversary of the Executive Order highlights how profoundly the environmental justice movement has transformed the face of U.S. environmentalism. As we look toward the future to address monumental environmental challenges like climate change, environmental justice activism must continue to reshape and connect the broader agendas of sustainability and social equity. (Rachel Morello-Frosch, Ph.D., M.P.H., Professor, Director Doctor of Public Health Program, Department of Environmental Science, Policy and Management & School of Public Health, University of California, Berkeley, CA)

Hope Diminished, the Executive Order on Environmental Justice12898 initially resonated among Environmental Justice Organizations, People of Color, and low-income communities as a sign of Hope and Justice for communities over-burden with environmental toxins and disproportionally impacted by polluters. Sadly, the EO pits Low-income communities, People of Color, with little to no resources against Corporate America; with the EPA taking a mediator position, in which case, the low-income communities and People Color are left to take on challenges beyond their immediate capacities, in terms of resources, technical support, scientific evidence, legal representation, and time. It is often a battle of divine hope and intervention from above that keeps the struggle a live. Environmental Justice communities deserve a level playing field for the insurmountable obstacles facing their daily lives. (Juan Parras, Executive Director, Texas Environmental Justice Advocacy Services, Houston, Texas)

The issuance of the Executive Order in 1994 reflected the culmination of organizing, raising awareness, and breaking through to policymakers. But it really just set the stage for the next twenty years of work that has followed. Progress has been slow but steady – and our goals keep moving. In California, for example, EJ groups have certainly tackled disparate exposures to hazards and poor air but they have also moved the needle on such cutting edge issues as transit equity, access to parks, and the very nature of the state’s response to climate change. And it is the recipe that brought us the Executive Order in the first place – strong community organizing, a solid base of research, and a sophisticated ability to play the inside and outside games – that will allow the environmental justice movement to continue to meet the challenges ahead. (Manuel Pastor, Ph.D., Professor, Sociology/American Studies & Ethnicity, Director, Program for Environmental and Regional Equity, Director, Center for the Study of Immigrant Integration, Los Angeles, CA)

This year we celebrate one of the EJ movement’s many proud achievements. We must also recognize that there is much more work to be done. I am eternally grateful for the leaders who have built this great movement and I join them with enthusiasm and renewed hope and commitment as they continue to move us forward. (David N. Pellow, University of Minnesota, Minnesota Global Justice Project, Minneapolis, MN)

President Clinton’s Executive Order on environmental justice was a handful of words that launched a thousand ships: federal and state agencies scrambled to figure out how to address it, polluters had a new uncertainty in their forward planning, and communities of color had a new tool with which to seek to gain redress against exposure to hazards. And yet to this day the executive order’s potential to bring environmental justice is still far from being realized. Twenty years on, it’s time for government and society to rededicate themselves to achieving environmental justice, locally, nationally, and globally. (J. Timmons Roberts, Ph.D., Ittleson Professor of Environmental Studies and Sociology Brown University, Providence, RI)

The many communities I serve are hoping to have the process result in strong policy guidance, standards and recommendations that can be enforced. Environmental justice communities are tired of being ‘sacrifice zones’ or ‘kill zones’ where the air, water and community are not protected. President Obama recognized this problem in his State of the Union and promised to do more to protect communities. (Michelle Roberts, Co-Coordinator, Environmental Justice & Health Alliance for Chemical Policy Reform, Washington, DC)

The Obama Executive Order on Environmental Justice reiterates the mandates of the first Clinton Executive Order and implies that environmental impacts and exposures on communities of color and low income are of critical concern. However, it represents a lost opportunity to have assessed the effectiveness of the prior order and to provide a stronger mandate for achieving, evaluating, and reporting progress by federal agencies on achieving environmental justice in the most vulnerable communities. It reveals a lack of vision for how those localities that bear a disparate burden of industrial pollution and our consumerism, can achieve the goal of healthy, sustainable, livable communities in which we live, work, play, pray and go to school. That goal is at the heart of our democracy and of the American Dream. (Peggy M. Shepard, Executive Director, Co-Founder, WE ACT For Environmental Justice, Heinz Award Recipient, New York, NY)

The signing of the EJ Executive Order marked a moment in time when the federal government signaled that social inequalities arising from environmental decision-making could no longer be ignored. The Executive Order was a triumph for activists who worked tirelessly to make their concerns about environmental impacts in their communities known and considered in the policy-making process. Despite limits on what can be achieved with an Executive Order, the EJ Executive Order fundamentally changed the way in which people thought about the environment in low-income and minority communities. (Dorceta E. Taylor, Ph.D., University of Michigan, School of Natural Resources and Environment, Professor, Environmental Justice Field of Studies Coordinator, Ann Arbor, MI)

I can clearly remember that day in Washington, DC, when we finished the proposal to present to President Clinton. It all came down to the Power of the Pen, after hours of drafting and redrafting the language, it all came down to the President when he placed his signature on Executive Order 12898. This was an historical moment captured in time that has helped changed the course of history in out fight for Environmental Justice through the “Power of the Pen.” (Rev. Charles N. Utley, Community Organizer and Campaign Coordinator, Blue Ridge Environmental Defense League/Hyde Park Improvement Committee, Augusta, GA)

It’s hard to believe that the Environmental Justice Executive Order is reaching its 20th year. As a community that started organizing itself to protect its children from environmental exposures at a local school, we did know that what we were fighting for was environmental justice. The Executive Order and Principles allowed our community to build their vision for our community. This vision included shutting down the dirty coal power plants in Chicago, demanding the clean-up of a Superfund site in our community and better public transit options. In 2012, we won the shutdown of the plants, building of a new park on the capped superfund site and implementation of a new bus line. While these campaigns were long, it shows the power of organizing for environmentally just communities. (Kimberly Wasserman, North American Goldman Prize Recipient, Community Trainer, Little Village Environmental Justice Organization, Chicago, IL)

As I reflect, it is significant to note that it has been twenty years since the signing of the Environmental Justice Executive Order. Since that time, on the one hand, much has changed; and then on the other, nothing has changed. The Executive Order brought serious attention to the disproportionate exposure of minority and poor communities to environmental pollution. That order triggered a response from federal agencies, by charging them to include environmental justice as a part of their missions. In addition, it created a mechanism for working together to address environmental justice issues through inter-agency working group (IWG). The executive order raised the importance of protecting the environmental health of minorities and the poor to the highest level in our government – the office of the President. Since that time, there has been an explosion within the research community, creating a huge body of literature and developing a unique field of study we have come to know as Environmental Justice; while turning the pursuit of its study and addressing its issues into the EJ Movement. The executive order made environmental justice a legitimate parameter within our government and resulted in the development of a structure and the creation of a process from within government to provide resources to agencies to address “disproportionately high and adverse human health or environmental effects on minority and low income populations.” We still have a long way to go. (Beverly Wright, Ph.D., Executive Director, Deep South Center for Environmental Justice at Dillard University, Heinz Award Recipient, New Orleans, LA)

As a member of the NYC Environmental Justice Alliance, UPROSE benefits locally from the technical/policy expertise and organizing support of our citywide collective. In Sunset Park, Brooklyn, our EJ work began by organizing to stop the onslaught of environmental burdens hoisted onto the lungs of our loved ones, but during the journey we successfully doubled the amount of open space, stopped the siting of power plants, made avenues pedestrian friendly, increased surface transit, retro-fitted diesel trucks, planted hundreds of trees, helped pass legislation addressing Brownfields, Solid Waste and Power Plants, got our young people into college and graduate school and built an intergenerational movement committed to addressing climate change and community resiliency- the work continues. (Elizabeth C. Yeampierre, Esq., Executive Director, UPROSE, Brooklyn, NY)