Before the Environmental Justice Movement burst on to the national scene, pollution in communities of color and poor neighborhoods was largely ignored by the media, industry, government, and green groups.

The environmental justice framework grew out of grassroots community struggles committed to a simple principle. That principle? That all people and communities are entitled to equal protection of environmental, energy, health, employment, education, housing, transportation, and civil rights laws and regulations. This year represents the fortieth anniversary of the 1979 Bean v Southwestern Waste Management Corp. lawsuit, the first of its kind to challenge discriminatory siting of a waste facility under civil rights law. African American homeowners in Houston began a bitter fight to keep a municipal landfill out of their suburban middle-income neighborhood.

Residents and their attorney, Linda McKeever Bullard, filed a class action lawsuit to block the facility from being built. I was an expert witness on the Bean case. My 1979 Houston waste study found a clear racial pattern in the city’s dumping: 82 percent of all solid waste disposed in Houston from the 1930s to 1978 was dumped in mostly black neighborhoods – even though blacks made up only 25 percent of Houston’s population. This pattern occurred in a city without zoning.

Four decades after Bean and the Houston waste study, researchers have found environmental injustice maps closely with Jim Crow housing segregation, bias decision making, and discriminatory zoning and land use practices. America is segregated and so is pollution. The equity lens is a useful frame for understanding the intersectionality of environmental, climate, economic and racial justice issues in the United States.

Millions of Americans have the “wrong complexion for protection.” Race is still more potent than income in predicting the distribution of pollution and polluting facilities. Even money does not insulate some Americans from pollution and environmental racism. African American households with incomes between $50,000 to $60,000 live in neighborhoods that are more polluted than the average neighborhood in which white households with incomes below $10,000 live.

African Americans are 79 percent more likely than whites to live where industrial pollution poses the greatest health danger. African Americans in 19 states are more than twice as likely as whites to live in neighborhoods with high pollution levels, compared to Hispanics in 12 states and Asians in 7 states.

African Americans are overrepresented in populations who live within a three-mile radius of the nation’s 1,388 Superfund sites. The percentage of African Americans living near the nation’s most dangerous chemical plants is 75 percent greater than for the U.S. as a whole, and the percentage of Latinos is 60 percent greater.

African Americans and other people of color breathe 38 percent more polluted air than whites. They are exposed to 46 percent more nitrogen oxide than whites. In 46 states people of color live with more air pollution than whites. African Americans are exposed to 1.5 times more pollutants than whites.

Residents living near dirty coal plants are more likely to suffer from respiratory illnesses than those living farther away. More than 68 percent of African Americans live within 30 miles of a dirty coal-fired power plant, compared with 56 percent of whites and 39 percent of Latinos.

Two million Americans live within three miles of the top twelve “dirtiest” coal power plants (76 percent of these residents are people of color). Each year between 7,500 to 52,000 Americans die prematurely from power plant emissions. This is comparable to the 40,000 Americans killed in vehicle accidents each year.

Polluting industries such as toxic waste facilities, high-risk chemical plants, oil refineries, and coal fired power plants have turned many African American and poor communities into environmental “sacrifice zones.” The nation has 150 refineries located in 32 states. People of color make up over half of the residents who are at greatest cancer risk from oil refinery pollution. Refineries dumping pollution on fence-line black and Latino communities is a fact of life along Houston’s Ship Channel, Port Arthur and Corpus Christi’s “refinery row,” Louisiana’s “Cancer Alley,” Southwest Detroit, South Philadelphia, North Richmond, CA and Los Angeles’ South Bay region.

African Americans need clean air, clean water, healthy food, high quality jobs, clean energy, green and affordable transportation, and access to safe natural environments. The Green New Deal Resolution is a positive first step that presents climate solutions to move the United States in the right direction toward a just clean energy economy for all—solutions that eliminate greenhouse gases, create millions of high-wage American jobs, build green and accessible public transportation, reduce poverty and inequality, promote equal protection of workers, frontline communities and vulnerable populations, and provide safeguards against climate and related environmental health threats.

Climate change will increase the number of “bad air days” and pose significant health threats, including cardiovascular, respiratory allergies, and asthma, with an unequal burden falling on African Americans. African Americans are almost three times more likely than whites to die from asthma related causes. African American children have a death rate ten times that of non-Hispanic white children; African American children are 4 times more likely to be hospitalized for asthma, as compared to non-Hispanic white children; and African Americans account for 13 percent of the U.S. population, but 26 percent of asthma deaths.

A disproportionate share of African Americans (55 percent) live in the South, a region where a disproportionate share of its governors and attorneys general are climate deniers who have routinely resisted stronger environmental protection and climate action. African Americans in southern states have not only had to fight environmental racism but have had to contend with state officials fighting the American Care Act (ACA) or Obamacare, Medicaid expansion, Clean Power Plan, climate adaptation plans and renewable energy standards. Ironically, many of these same climate-vulnerable southern states have the highest poverty and highest electricity bills. They also have the highest uninsured rate, unhealthiest residents, and the shortest life expectancy.

Climate change will widen the racial wealth gap. Structural racism is a major factor creating the wealth gap between black and white families. Black wealth is roughly one tenth of white wealth. In 2016, the median wealth for black and Hispanic families was $17,600 and $20,700, respectively, compared with white families’ median wealth of $171,000.

A recent study of Hurricane Harvey found storm-induced “flooding was significantly greater in Houston neighborhoods with a higher proportion of non-Hispanic Black and socioeconomically deprived residents.” However, disaster recovery dollars do not always follow need. The way FEMA aid gets distributed increases racial inequality. A Rice University and University of Pittsburgh study found counties that experienced $10 billion disasters, white communities gained an average of $126,000 in wealth following recovery efforts—while black and other communities of color lost between $10,000 and $29,000.

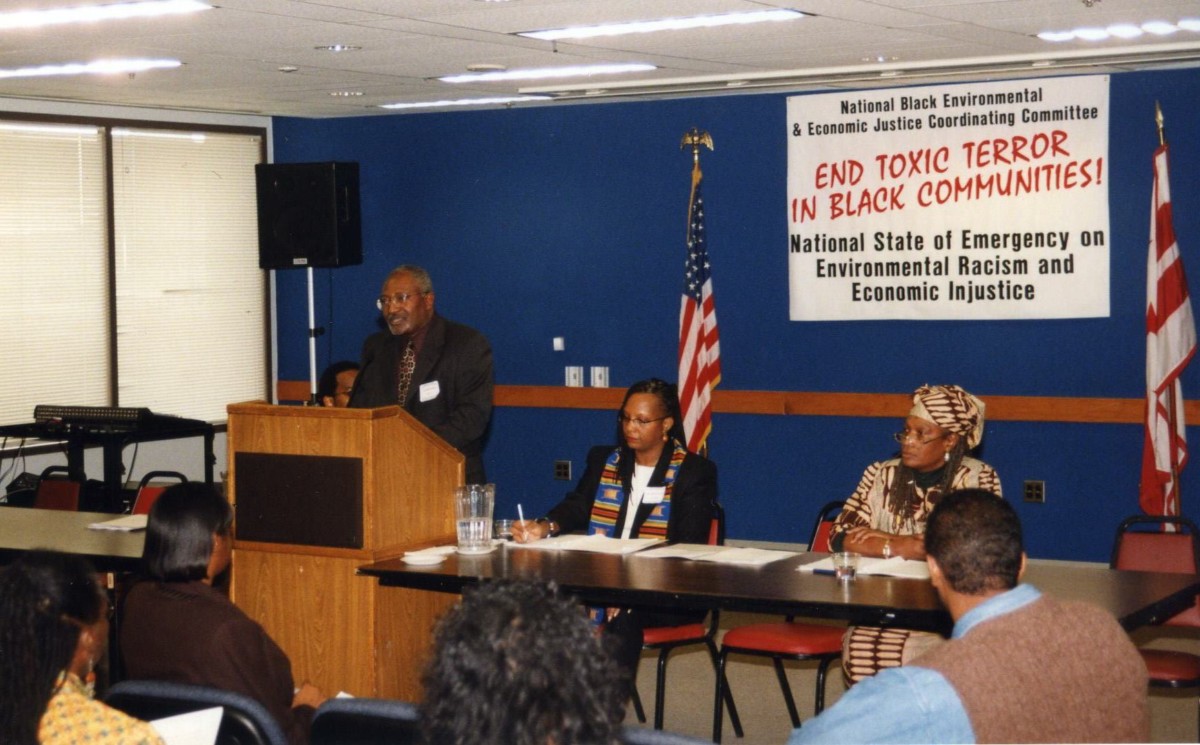

Diverse black organizations—including the NAACP, the nation’s oldest civil rights organization, black colleges and universities, grassroots groups, labor, faith organizations, entertainers, youth and students, and a host of other black organizations—are calling for environmental, climate, economic, energy and racial justice. Many of these organizations, coalitions, networks and consortia are committed to making America a much stronger, healthier, and fairer nation. We are stronger together when people who have the most at stake are part of the decision-making on how we move forward to heal our communities, our states, our nation and our planet.

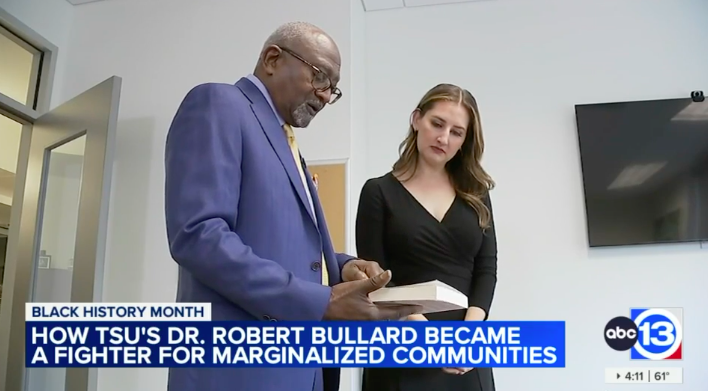

Dr. Robert D. Bullard is featured in HBO Original Six-Part Documentary Series

Dr. Robert Bullard, the creator of the environmental justice movement,...